by Claire Doole | Nov 20, 2022 | Speechwriting

One of the most common refrains I hear when coaching senior leaders in public speaking is they have to rewrite most of the speeches drafted for them.

Much of the time the person struggles to deliver the speech because it has not been written for them. In the words of one agency head, “it doesn’t capture my voice.”

I have written many speeches. I see my job as writing the speech that the speaker themselves would write if only they had the time. I have to stand in the shoes of that person and see the world as they see it.

Below are some tips based on how I capture my speakers voice.

Research

Listen to recordings of the speaker at events and conferences. If you are a staff member observe the speaker at town hall meetings or during internal webinars.

Get to know your speaker

You must have access to the speaker so that they are involved in the drafting process. During a phone call or in-person meeting, together, you will first have to define the purpose, audience and argument of the speech. But don’t forget to drill down on the essence of that person – what drives them? What are their beliefs? What type of person are they?

You can often find out a lot about people by asking them about their motivation for doing the job they are doing or the lessons they have learnt through success or failure. These sorts of questions typically elicit stories that give an insight into the person.

Record the conversation so you can play it back and become familiar with their voice

Identify their speaking style

When listening to the recordings from your research and meeting, ask yourself these questions:

1. Is the speech in their mother tongue? Or a foreign language?

2. Are they a fast or slow speaker?

3. Do they prefer long or short sentences?

4. Do they like simple or sophisticated words?

5. Is there style plain or florid?

6. Do they use metaphors and analogies?

7. How do they structure an argument? Do they get to the point and

then explain how and why or do they lead up to the point?

If you are writing for a non-native speaker, then make sure that you don’t use words that that they can’t pronounce. I once had a speaker who could not say the “ch” as in climate change, which was a shame as he was head of an environmental agency. So, we would use climate crisis or emergency instead.

Write for the speaker

It is very tempting to write for yourself, so guard against this by playing the recording of their voice. You need to hear the speaker’s voice in your head as you write. If they use a lot of intensifiers like “really”, “extremely” “hugely” then you need to reflect that, bearing in mind though that they might start to sound like King Charles!

Read it out loud

This may seem to contradict my previous point. But you will soon see if the argument stands up, if the ideas are too repetitive or if the sentences are too long for anyone to say with impact.

A speech is not written in a day. It needs to be honed and validated by the speaker so it not only says what they want to say but also sounds like them.

If you follow these tips you have less of a chance that the speaker will go off script or announce with a flourish that they are discarding the speech you have carefully crafted!

by Claire Doole | Oct 9, 2022 | Blog, Speechwriting

What is the first thing you think about when asked to give a presentation or speech?

That is a question I often ask in my presenting and speechwriting workshops.

The answers are often very candid but very wrong. They range from the slides I can recycle from previous presentations to structure and messaging.

You can’t give an impactful presentation or speech until you have worked out who you are talking to. Too many speaking engagements are wasted opportunities because the speaker has not tailored his or her content to the audience. If you give some off-the-shelf presentation, audiences know that you are speaking at them and not to them, and will, often, zone out.

You need to ask yourself three questions:

1. What does my audience know about the topic of my speech?

2. What is their attitude to the topic?

3. How big is the audience, and what is the setting?

Know your audience

The audience will likely be a mix – some know more, others less. In this case, you need to speak so that everyone in the audience understands what you are saying. Albert Einstein once said, “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” It is worth taking the time to do this, as the spoken word must be simple as the audience, unlike the written word, must understand it immediately.

Audience attitude

If you are facing a hostile or skeptical audience, you must select your arguments and supporting evidence carefully. I often advise to connect immediately with this type of audience by addressing the concerns they may have. If you work for an oil company and are addressing environmental activists, you have to have the right level of humility, as you can easily be accused of greenwashing.

However, even with a favorable audience, you should think about what motivates them, what arguments they will find convincing and what are their biggest concerns. Here it is vital to tap into what is in it for them in terms of reward or the risk of not doing something.

Size and setting

If the audience is large and the setting formal, the style of your speech is likely to be more formal and rhetorical. If a smaller audience, particularly if you know them well, your tone should reflect this. In any case, you should think conversational rather than declamatory.

The setting – where the presentation takes place – is important as it may give you a way of connecting with the audience by referring to it. Similarly, assess how important the occasion is, as this will impact the tone and style of your speech.

It may seem like a lot of work, but it will pay off as audiences really appreciate a speaker who realizes that a successful presentation or speech must be audience- centric.

by Claire Doole | Jul 16, 2018 | Blog, Speechwriting

Recently, I coached the head of a large Swiss NGO for a series of speeches she is giving at a popular summer forum.

We worked on a structure and delivery that holds the attention of a global audience from different backgrounds – academic, non-governmental, diplomatic and corporate.

What the coaching reminded me of is that the theories on memory recall developed by a German Professor during the last century are still valid today. Namely, the ability of the brain to retain information decreases over time.

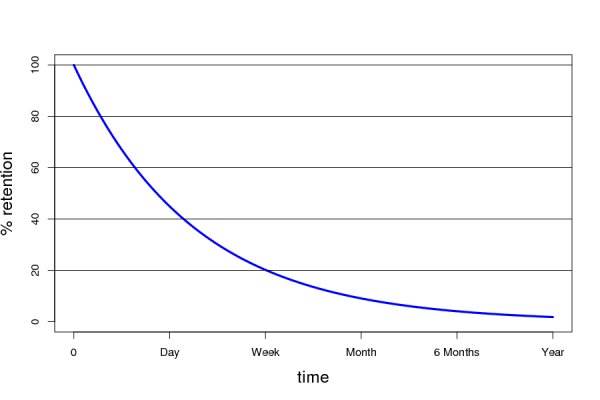

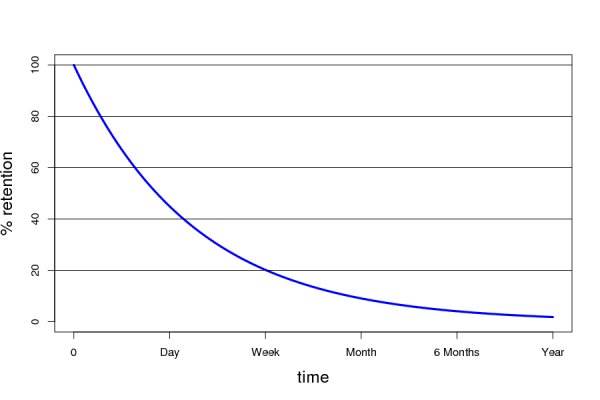

Professor Hermann Ebbinghaus developed the “forgetting curve” which shows that the sharpest decline is during the first 20 minutes and then it levels off after 1 day. The speed of the decline depends on a number of factors such as how easy, visual or relevant the information is to retain. However, on average as the graph below shows people only retain 40% after the first day.

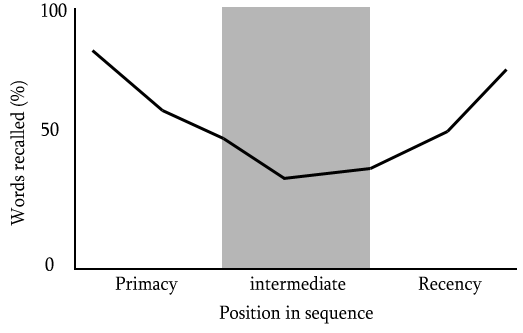

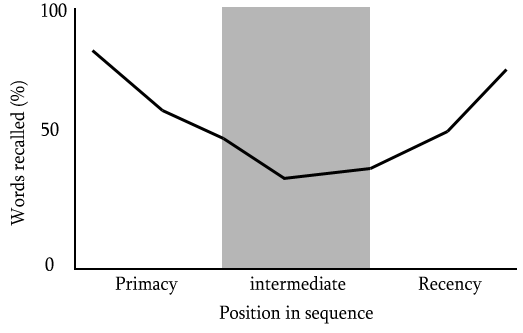

He also developed the concepts of primacy and recency – that we remember the first things and last things we are told with a good chance of forgetting much that is in the middle.

Theory into practice

Armed with this knowledge, she constructed a speech that put the overarching key message in the introduction and then developed 3 related key messages in the body before recapping them at the end.

So did the audience remember the key messages?

I asked people at the forum a couple of hours later and they clearly remembered the introduction – about the rise of xenophobia and restrictive immigration policies in Europe and the US and the call for fundamental rights to be respected.

However they only remembered the messages in the body of the speech when prompted. This may have been because the introduction focussed on a problem that was familiar to the audience and the body on innovative solutions to that problem.

Whatever the reason, it showed that when writing a speech the author has to frontload their key messages to be sure that they are remembered.

The next day, I asked several people what they remembered and true to Ebbinghaus’s theory they recalled the introduction but even less than the day before. The explanations ranged from battling jet lag, the time of day (late afternoon), listening to a foreign language to the temperature in the room (28 degrees outside).

When I tested their recall of the other opening speeches, the results were dismal. They remembered very little a couple of hours after and nothing on the second day.

It has to be said that I remembered very little either, as the speeches were not audience centric and certainly not structured according to the Ebbinghaus principles.

So, however engaged and educated your audience may be, it is worth remembering that it is your responsibility as the speaker to hold their attention by delivering a clear structure with memorable key messages.

SUBSCRIBE TO CLAIRE'S BLOG

by Claire Doole | Feb 27, 2017 | Blog, Speechwriting

Photo caption: H.E. Mr. Didier Burkhalter, Federal Councilor and Head of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of Switzerland, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, speaks during the High-Level-Segment of the 34th Session of the Human Rights Council. UN Photo / Elma Okic

I am watching closely as the 34th session of the UN Human Rights Council starts in Geneva. I am hoping that some of the diplomats I trained recently in public speaking for the UN Institute for Training and Research (http://unitar.org) are going to read their statements with impact.

As a former BBC Geneva correspondent I used to cover the Council and despair of finding a clip that I could use of a diplomat who was sounding natural and looking confident. Most of them would read their statements looking down at their text and in a monotonous tone.

I accept that sometimes diplomats don’t want to draw attention to their statements or at least not find themselves on the BBC news. However, often, on an issue as important as human rights, they do want to stand out and make their voices heard.

So, what are the techniques for making sure that when you read a prepared text such as a speech or a statement, people sit up and listen? By the way, these tips apply whether you are a diplomat or not!

One of the best ways to project confidence when speaking in public is to follow a technique mastered by some of the great public speakers – Ronald Reagan, Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill.

They all managed to read a speech, sounding conversational and unscripted, using a technique known as “See-Stop-Say“.

First of all print your text in large font with double spacing. Make sure that the sentences are short – ideally not more than 10 words so that your eye can absorb them easily. You may want to put key words in bold, as this will help you with emphasis and rhythm.

Practice speaking in the following way:

- See – see each phrase and “record” a picture of it with your eyes. Instead of reading the whole section, let your eye “record” only the phrase or part of the phrase that you can commit to memory.

- Stop – look up from the page and pause.

- Say – say the phrase out loud from visual memory. Pause again before looking down to memorise the next phrase.

Pausing is the key to this skill. Pauses

- Help you remember the phrase

- Allow the audience time to digest your ideas

- Punctuate your sentences

- Build anticipation.

The great American jazz musician, Miles Davis, once said, “in music, silence is more important than sound”.

This applies to public speaking too. Pausing is your best way of sounding authoritative. It automatically gives you “gravitas”. And, if you have a key phrase or message, pause before and after it for increased impact.

Rehearse, Rehearse, Rehearse

When I am preparing managers, executives, and CEOs to deliver keynote speeches, they are always amazed when I tell them that professional speakers, journalists, and moderators, always practice their first 20 seconds. It is the moment when you are most nervous so it calms the nerves if you know what you are going to say.

If you watch TV journalists before they go live, you will see that they are walking to and fro (movement aids recall) preparing their first answer.

It is always important to practice reading out loud your statement or speech so you become familiar with it. If you can remember the first 20 seconds that will also help as you can keep eye contact with the audience before you follow the “see-stop-say” model.

If you are delivering your remarks on stage, choose five spots in the room, which form the shape of a W – practice making your points to each spot. This will ensure that you include everyone in the room – even those on the sides who are easily ignored.

If you are reading your statement seated, like the diplomatic delegations at the UN, then you need to look up and straight ahead. The UNTV cameras will focus on you and the journalists, who receive the video footage, will be delighted as they will have a wealth of clips to choose from as you deliver your statement with impact.