by Claire Doole | Sep 5, 2023 | Blog

After the summer break, we are now back in the world of webinars, hybrid and in-person events.

I am being asked to moderate panel discussions – sometimes four or five consecutively on the same day – each with far too many people to have a real discussion. And if they are discussions and not “panel presentations”, they are far too scripted, predictable, and tell the audience little if anything they didn’t already know.

Audiences tell me that most panels are pointless. I would agree unless they are well-moderated, audience-centric, and have the right speakers for the subject.

It was therefore a joy in June to see a wonderfully moderated panel discussion at the Better Cotton Conference in Amsterdam where I was the Master of Ceremonies.

Hats off to Antonie Fountain from the Voice Network and Ashlee Tuttleman from the Sustainable Trade Initiative for leading a dynamic and innovative session on sustainable livelihoods. Here is what they did so well:

• Antonie showed that you can take a serious subject and make it engaging. Through great use of simple visuals (slides for example with one word on them) plus video clips from Monty Python and Indiana Jones, he gave us a captivating keynote about the lessons learned from the cocoa industry in building more sustainable livelihoods.

© Dennis Bouman – Contact before commercial use

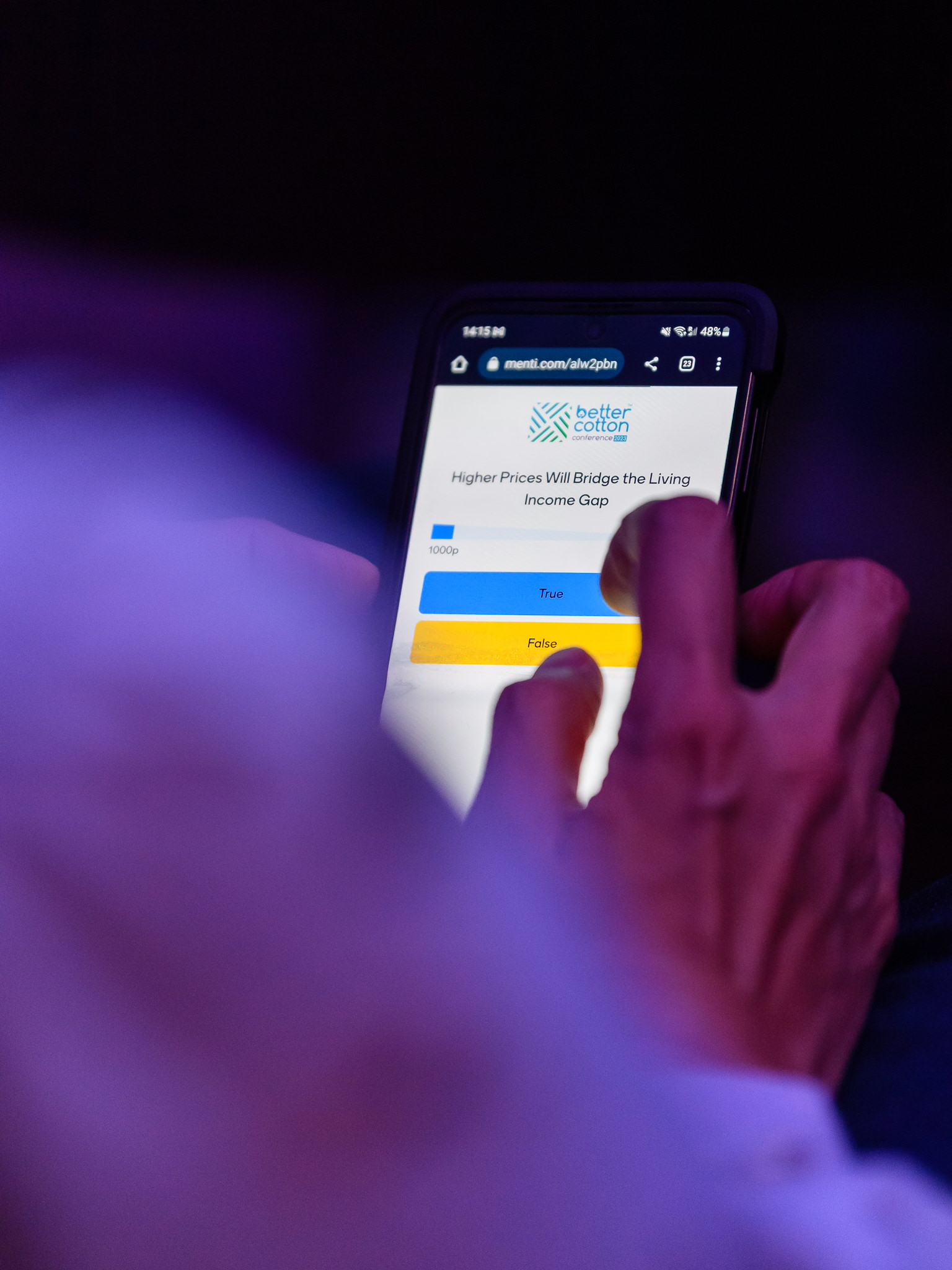

• He and Ashlee then kept up the pace and energy by running a 20-minute quiz on Mentimeter for the online and in-person audience in which they debunked five myths about sustainable livelihoods.

© Dennis Bouman – Contact before commercial use

© Dennis Bouman – Contact before commercial use

• And then the “piece de resistance”. They asked the three winners of the quiz to come on stage for an impromptu panel discussion.

© Dennis Bouman – Contact before commercial use

• The panelists were great, proving that often the real knowledge lies with the audience!

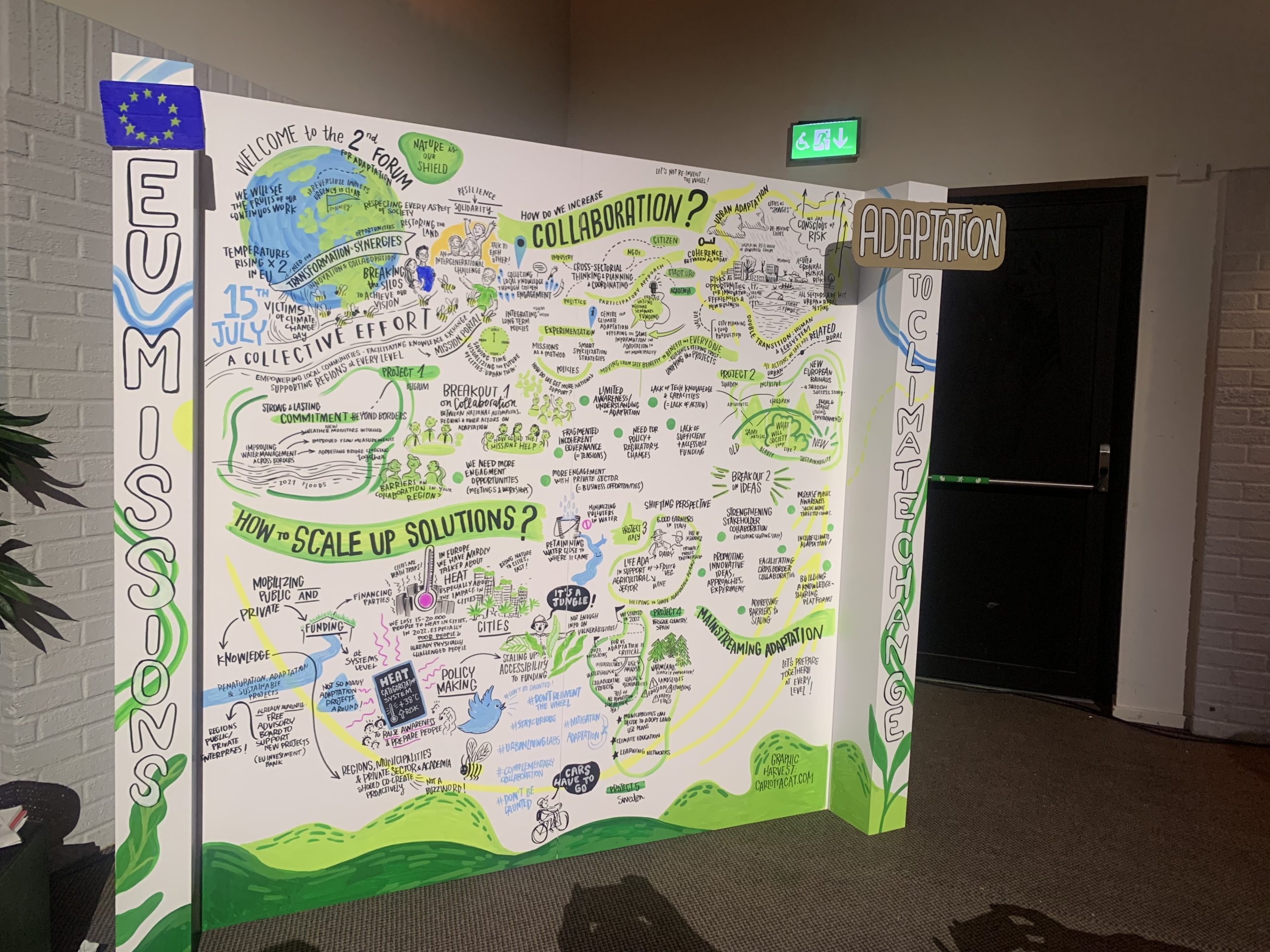

In fact, the 2-day conference was packed with variety and different formats to keep the audience engaged, and most importantly entertained. As you can read here, they also elevated their event by engaging a graphic artist.

If you are running an event or panel discussion, I would be delighted to advise on how to make it something that the audience will always remember. I can also train your teams to moderate and MC, in case you don’t want to employ a professional moderator!

by Claire Doole | Jun 28, 2023 | Blog

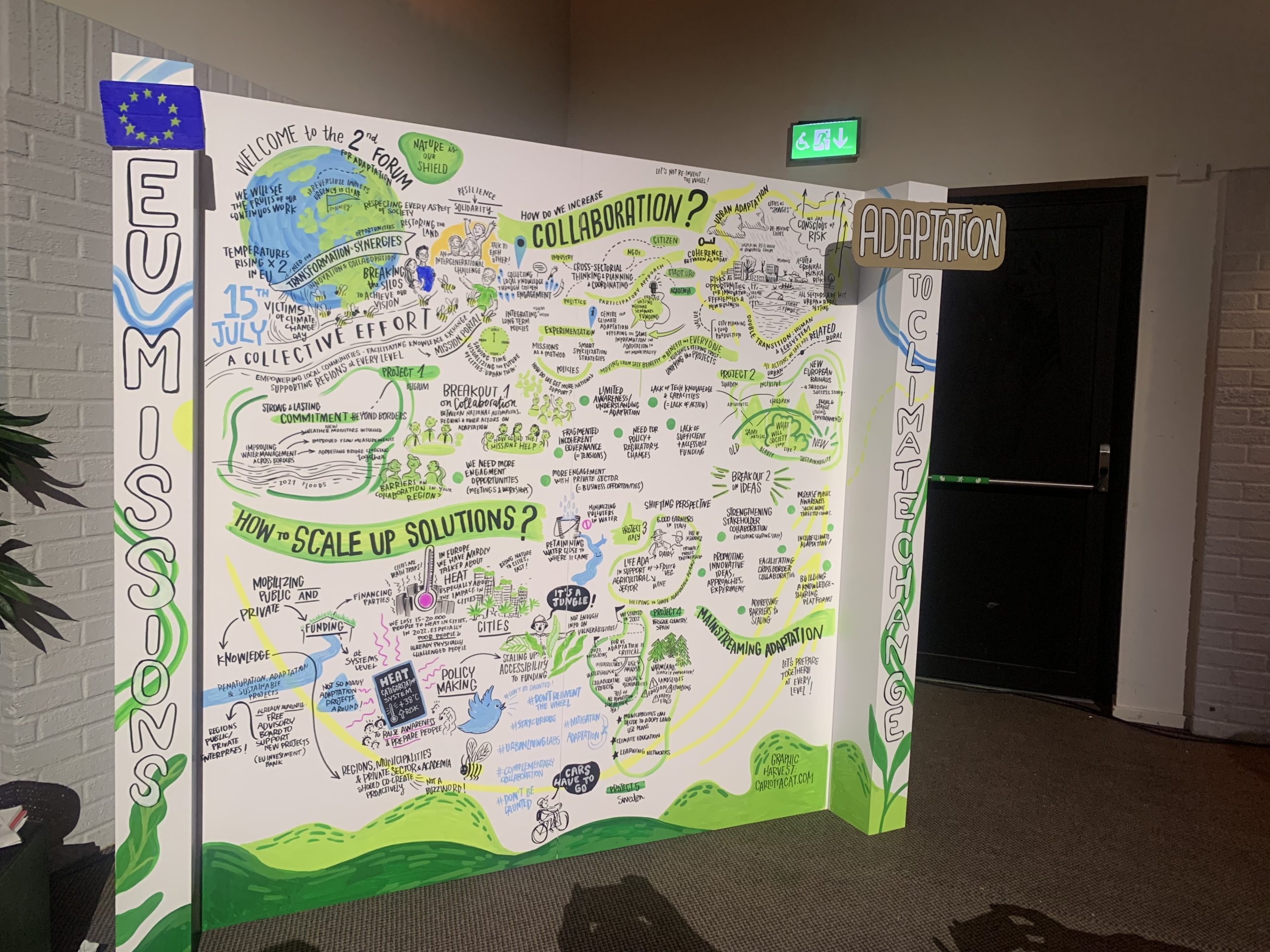

Many of us are visual learners and images definitely aid recall. So, it is surprising that not more event organisers engage graphic recordists.

They visually map conversations illuminating what is essential in real-time.

“People learn by looking and reading and they will remember things better if all of the senses are engaged”, says Carlotta Cataldi – who for the past 13 years has been bringing ideas alive visually at conferences and meetings.

Carlotta draws on paper, on what is called a knowledge wall, as well as digitally.

Having worked with her twice over the past few weeks at events where I was Master of Ceremonies, I saw how deeply she listens, and how rapidly she visualizes complex concepts.

She has developed her own language – bees represent a cross-pollination or cross- fertilization of ideas, a thermometer refers to rising heat in cities, while wellbeing is visualized not as a coin i.e. money but as a jewel.

For the audience there are multiple advantages. It helps keep their minds focused on the content of the discussions. It helps to animate conversations, and provides them with an engaging visual summary of conference discussions to share with colleagues and on their social media channels.

A resource for organisers and the Master of Ceremonies

As a Master of Ceremonies or panel moderator, you are trying to bring clarity to the conversation in real-time. Carlotta goes one step further and turns that clarity into something visual – a mix of images and key messages.

It is, however, a team effort. I always introduce the graphic recordist to the audience at the start of an event and then, depending on time, I bring them in before coffee breaks and lunch and at the end of the day.

Sometimes, I may even ask the recordist to join me on stage to tell us what was important for them in the conversation. Each time, I am encouraging the audience to go and see what the recordist has done as this reinforces engagement.

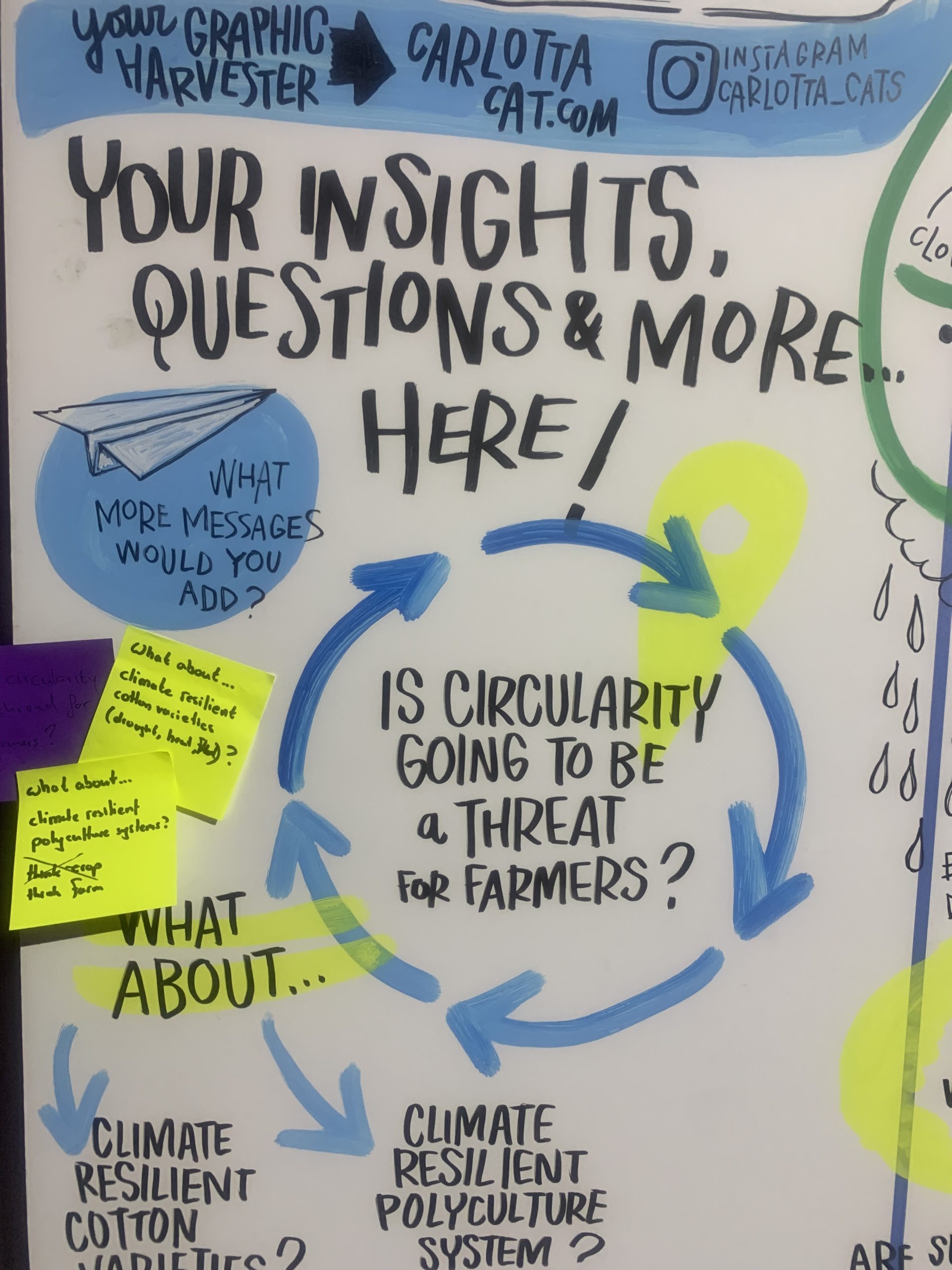

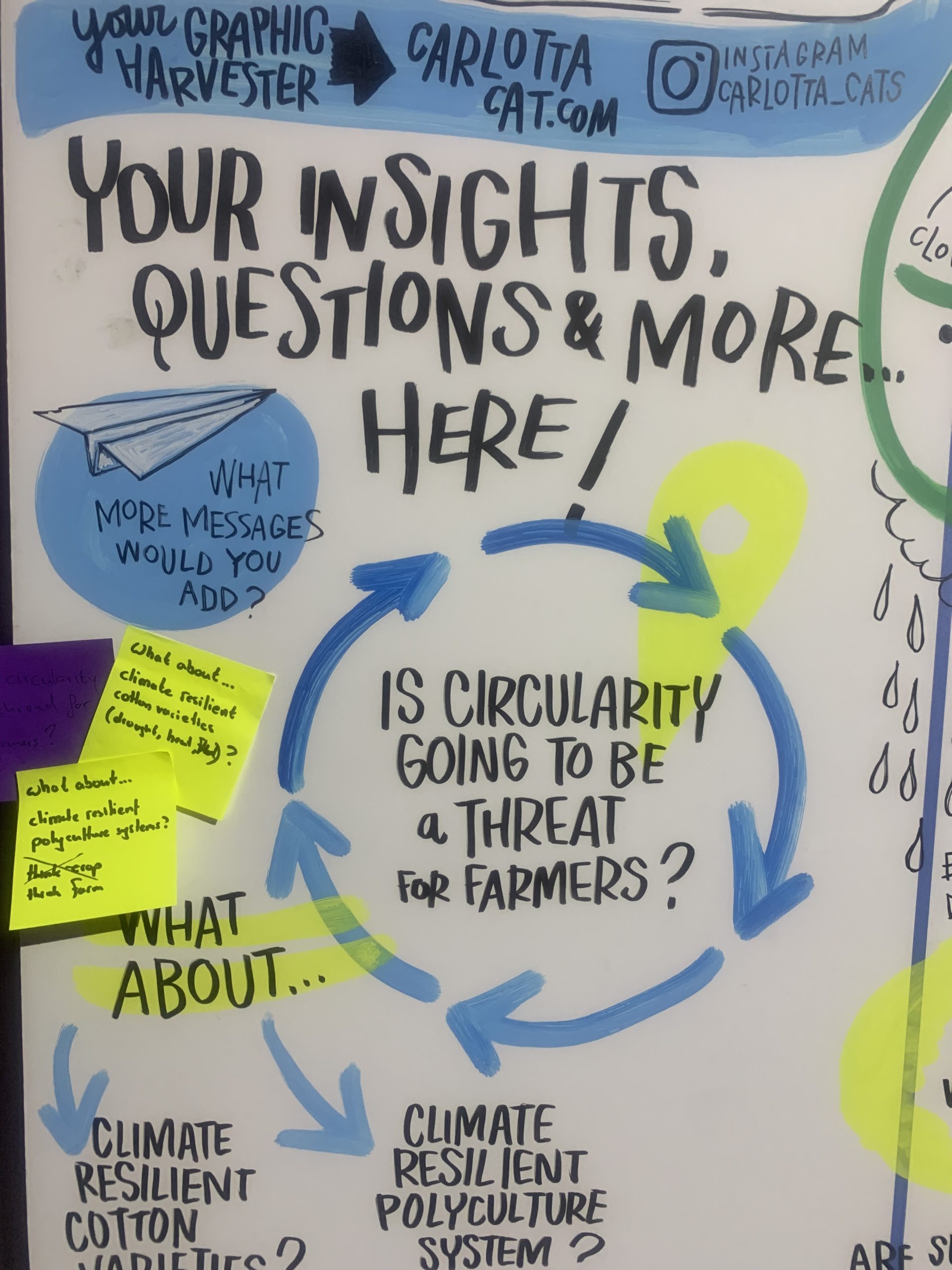

At an event for Better Cotton last week where I was the Master of Ceremonies, we went one step further and encouraged the audience to write their insights or questions on post-its and tell us if anything was missing from the board or anything they wanted to draw.

Organizers can often underestimate an audience’s need to be entertained and to participate in the conversation. Engaging a graphic recordist is a great way to ensure audience participation and make the event is more audience-centric and memorable. The images also are a great resource for post-conference reports and can be digitalized for use in PowerPoint presentations and webinars.

“I love my profession”, says Carlotta, “as it brings beauty and natural curves, a human touch to a business event.”

Claire Doole runs workshops on how to organise events and moderate panel discussions.

by Claire Doole | May 1, 2023 | Blog

As soon as the sound failed in the opening video, I knew the conference would be rock and roll. Fortunately, I had insisted on an earpiece. I told the hastily assigned director to put the video volume up and he subsequently told me in my earpiece when the last-minute replacement for the opening speaker had entered the room. In fact, he arrived too late to start the conference. It was just as well that I had minutes beforehand lined up the second speaker to open it.

And that is how the day went, constantly adapting the programme when speakers didn’t turn up, physically changing the number of chairs on the stage before each session and repeatedly checking the number of available microphones and whether they worked.

In theory, acting as the Master of Ceremonies,(MC) is less work than moderating panel discussions, which take a lot of preparation to do well. An MC’s job is to make sure the event goes smoothly, linking the sessions and speakers and engaging the audience.

But if there has been no technical rehearsal the day before, and the team is a team of experts in their field but not in organising events – a situation I often face – the MC can find themselves in charge of a salvage operation – papering over the editorial and logistical cracks on the day as best they can.

So, here are my top tips for event organisers on what to look for or do when engaging a Master of Ceremonies:

• Bring in the MC a couple of months beforehand. An MC can advise on the event flow editorial narrative and how to make the programme interactive and varied. As I have said before, it is hard to manage the audience attention span when there is one speech or presentation after another, often with no editorial coherence or one-panel discussion after another, which has the same format. (See my blogs on panel moderation here)

• Brief the MC on the overall purpose of the event, each session’s objectives, and the speakers’ rationale and structure so he or she can clearly communicate this to the audience. The MC is there to serve as a thread linking the content throughout the event.

• Make sure the MC is concise and compelling in his/her remarks. Audiences don’t like verbose MCs that take up too much space. The role is to facilitate, not dominate!

• Engage an MC who can weave a narrative through the event, clearly connecting the speakers and themes of different sessions.

• Check that the MC can improvise when faced with technical challenges or unexpected changes to the programme. Broadcast journalists are usually adept at this as they are used to keeping the show on the road.

• Engage someone with great time management skills as audiences appreciate an event that is kept on track and to time.

• Hire an MC who can handle questions from the audience with aplomb. They must be encouraging yet control the situation if the question is unclear, too long or not a question but a long-winded comment.

• Search for an MC with high energy levels, an ability to connect with the audience and a sense of humour. The latter is particularly important when faced with technical gremlins, speakers that go over time or audience members who can’t ask concise questions.

• Organise a technical rehearsal the day before the event, as anything that can go wrong will go wrong (Murphey’s Law).

Once, a jury member at an awards ceremony I was hosting was on the verge of announcing the winner – not realising that his role was to only talk about the selection process and that it was the European Commissioner – sitting in the front row – who would do the honours.

Fortunately, I managed to stop him before he named the winner – and the award (unlike at that infamous Oscars ceremony) was given to the right person at the right time!

If you would like advice on organising an event, do get in touch, as I run in-person and virtual workshops to ensure your event is engaging and insightful.

by Claire Doole | Feb 28, 2023 | Blog

Most of the people I coach do not write their speeches. They rely on a speechwriter who either fails to capture their voice or delivers a text that has been written to be read, not spoken.

This makes it incredibly difficult to deliver in a natural and convincing way.

Most senior professionals (or leaders) prefer to speak from briefing notes with key points, as this allows them to convey these ideas in their own words.

But sometimes, they have to deliver a keynote speech in a formal setting and cannot go off script.

So how to do you get your points across but not sound scripted?

Speak to the audience, not read to them

Have a look at this extract of a speech that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Turk, recently gave at the Martin Ennals Award Ceremony in Geneva.

I was in the audience as I coached the three awarded human rights defenders for their remarks to the media and at the ceremony.

Cérémonie de remise du Prix Martin Ennals 2023, 16 février 2023, salle communale de Plainpalais. Photo David Wagnières

I was really struck by how naturally the High Commissioner delivered his remarks and felt he was speaking to me and not at me. What was he doing to captivate the audience?

• Firstly, he had a conversational tone as if he was speaking to someone he knew.

• Secondly, he built a connection with his words to the people in the room, praising their tireless efforts to give a voice to the voiceless.

• Thirdly, he matched his tone and words with his body language, making eye contact with the audience.

How often do you see this? I observe a lot of speakers, and believe me, it is very rare. Most of them fail to align their voice, body language and words – and many of them rarely look up when speaking.

If you watch the whole speech of the High Commissioner

you will see that he is looking at the audience as he makes and expands on the same point. He looks down only to remind himself of the next point and then looks up again to deliver it.

It is a technique known as SEE-STOP-SAY and was used by Ronald Reagan, an actor who became a US President. I go into more detail in this blog.

It takes some practice, and the High Commissioner doesn’t always do it. However, he is so much better than the speakers who look up at the audience mid-sentence or at a random moment which has no connection with the thought they want to convey.

I have trained diplomats making speeches in very formal settings, such as the UN Human Rights Council, in this technique, and it really makes the audience sit up and listen. And as for the speaker, it helps them come across as approachable, accessible and authentic – qualities that are key if you want to be a great public speaker.

by Claire Doole | Jan 15, 2023 | Blog, Organising events

The head of an organization that last year ran more than 100 panel discussions asked me that question recently. By the way, if you think 100 is a lot, the organization had topped 150 panel discussions in 2020/21!

We all understand the quest for visibility, but sometimes less is more. The organization in question understood this when at COP 27 in Sharm El Sheikh last November it had to cancel a panel discussion – one of 15 it was organizing – due to a lack of audience.

Lack of audience

I was told by friends who attended COP 27 that there was marquee after marquee, side event after side event, but many of them were not full. One private company held a panel discussion at which only three people turned up.

This, I would argue, was an event that should have been cancelled, as it is not good for the organiser’s reputation, brings little benefit to the speakers, and is an uncomfortable experience for the audience.

Ironically, this is more likely to happen at big events like COP as there is more competition for attendees. This is having a knock-on impact on panelists in that they are being asked to speak at too many events, and there is not always enough of them to go around. Another international organization fielded requests from 80 side-event organizers for speakers – many of which they could not accept as they didn’t have that number of speakers available.

Lack of speakers

It can be challenging, particularly when organizing week-long events on a specific subject, to find enough speakers as there are sometimes only so many specialists. Organizers then turn to their B and C lists, which means speakers who are not so well-informed and are limited to the points they can or want to talk about.

In the past, speakers have grabbed the opportunity to be on a panel, whether for visibility or vanity, but organisers are reporting a new trend – the great panelist pullout. Panelists are either pulling out – often at the last minute – due to other commitments, suffer from panelist fatigue or because they see the low audience figures registered.

Countering the “cancel culture”

In the competitive world of events, organizers have to design and deliver an event that draws in audiences. Rather than limiting their thinking to speakers or subject, they need, for strategic reasons; to be more audience-centric – what is in it for the audience.

This means designing an event that first considers who are potential audience members and will the subject or theme capture their interest, either through possibly delivering best practices, offering new insights or helping them understand better the issues at stake.

After thinking first about how you will inspire or instruct the audience on topical issues, the next critical step is the casting – speaker selection. What are the criteria for choosing an effective speaker?

My question is always, what does a selected speaker bring to the discussion? Are they good communicators? How will the panelists interact with one another? This means that organisers need ideally to start the process of speaker selection a month to six weeks before the event, rather than leave it to the last moment.

Once you have your speakers, you need to explain to them why they are being invited and the questions they will be asked.

Similarly, organizers should not bring in the moderator in the final stages, but use their expertise in establishing the editorial flow for an engaging discussion even before contacting potential speakers. Many professional moderators are former or current broadcast journalists and know not only how to generate but also design a discussion that is productive and insightful for the audience.

I have reviewed these steps in more depth in previous blogs, but are worth recalling as we look at the weak links in panel organization.

In conclusion and to answer my friend’s question, you will be less likely to be put in the difficult situation of cancelling a panel discussion if it is well thought out, with the right speakers on the right subject at the right time.

Let’s hope in 2023 organizers don’t even have to consider cancelling a panel as they have realized the importance of quality over quantity!

Other blogs to read on organising events:

https://www.doolecommunications.com/successful-virtual-events-are-good-television/

https://www.doolecommunications.com/professionally-producing-virtual-events/

https://www.doolecommunications.com/has-there-been-an-event-reset-since-covid/