by Claire Doole | Nov 20, 2018 | Blog

A TED talk is all about sharing an inspiring idea. It sounds easy enough, but it is more difficult than you might think.

I speak from experience – having coached speakers for several TEDx events in Geneva and Lausanne and having been called in twice to salvage someone’s TED talk within days of the event!

So when I was asked by the UN to coach 9 speakers for their PlacedesNationsWomen event one of the first things I did was to write a guide on what makes a TED talk different from the usual presentation or keynote address.

Here are my tips on drafting the talk, based on my experience as a professional public speaker/ coach and the wonderful book, “TED Talks – The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking” by the head of TED, Chris Anderson.

- Make it personal: As a speaker, talk about an idea that matters deeply to you and transmit the idea and the passion you feel about it to your audience. It has to be an idea worth sharing!

- Know the audience: Think of yourself as a tour guide taking the audience on a journey to a new place. You need to begin where the audience is and steer them clearly and compellingly along the way.

- Stick with your idea: Think of your talk as about an idea rather than an issue. This is particularly important if you are tackling a tough topic where compassion fatigue can easily set in. An issue-based talk leads with morality. An idea based talk leads with curiosity. It says, “isn’t this interesting?” rather than “isn’t this terrible?” For example, this is an issue: Education for all. An idea would be framed as “Education’s potential is transformed if you focus on the amazing (and hilarious) creativity of kids.

- Connect the dots: You need a connecting theme, which ties together each narrative element. It is the idea that you want to construct in the minds of the audience. Can you put this in no more than 15 words?

- Make it memorable: Think about the three points/messages that you want the audience to remember when they leave the room. Studies show people rarely remember more than three points and recall drops dramatically after the first day.

The structure

Choose a structure that most powerfully develops your connecting theme. See below some suggestions, which can be mixed and matched over the talk.

- Personal journey: If you are sharing your personal journey then you may want to follow the classic “hero’s journey” structure where you have a goal but meet challenges along the way which you overcome and resolve the best you can.

- Persuade: If you want to persuade an audience that the way they currently see the world isn’t quite right, you will want to guide them through your argument so that is it plausible. This means breaking down your argument logically into small steps, perhaps even taking the counter position to show that it is flawed.

- Detective: Another way to build a persuasive case is to play detective. You start with a puzzle and then with the audience search for solutions, ruling them out one by one. You invite the audience on a process of discovery. This can work well if you are a scientist or researcher talking about a discovery you have made.

- Aspirational: You may want to speak of the world not as it is, but as it might be. You paint a picture of the alternative future you want and compare and contrast it with the situation today. (Think Martin Luther King, “I have a dream”.)

Techniques to make your talk memorable

- Open with impact. Within the first minute, you need to get the audience’s attention, make them curious and excited. Here are some ways to start.

- A surprising statement, fact or statistic

- A surprising rhetorical question

- Show a compelling slide, video or object

- A personal story or anecdote

You want to tease, but don’t give away your punch line. If you are looking to persuade or reveal a discovery you want to build up to your revelation.

- Close with impact.

- Move from the specific to the broad

- Call to action – invite people to take action on your idea.

- Personal commitment – make a commitment of your own.

- Values and vision – can you turn what you have discussed into an inspiring or hopeful vision of what might be?

- Narrative symmetry – the human brain likes balance so you may want to link back to your beginning so that the narrative comes full circle.

In my next blogs, I shall take you through how to align delivery and content as well as lessons learnt from my TED journey.

by Claire Doole | Oct 14, 2018 | Blog

Rapport is the foundation of influence and impact. An American psychiatrist and psychologist, Milton Erickson, once said, “With rapport, everything is possible. Without it, nothing is possible.”

So what is this magical ingredient in effective communications? It is about being on the same wavelength as someone else so that we feel connected. It often involves having shared values, beliefs or similar life experiences. I know, for example, that I usually instantly connect with someone who is or has been a journalist due to my time at the BBC.

But how do you build rapport with an audience made up of many different individuals? This is vital when you are speaking in public presenting, giving a keynote speech or sitting on a panel at a conference.

Many of the things that you do naturally one-on-one are applicable, such as finding common ground, asking questions and actively listening to what they are saying.

But when you want to build rapport with an audience, you need to use these skills more consciously.

Let me explain by sharing my list of how to do it, based on my experience as a moderator and public speaking coach.

Finding common ground

When you prepare your speech or remarks you need to think about your audience first and foremost. What are their needs, expectations and challenges? Far too often presenters think that communication is a one-way process but to have impact you need to ensure that your message has got across to the audience so that they are not only engaged but also feel, say or think differently as a result of your presentation.

Reading the room

I am often asked by people I coach/train how do I know that my message has landed. Well, the first thing is to read the room. Are people looking at you or reading their emails or looking out of the window? If they are looking at you, how are they looking – quizzically or in agreement? Do they have their hand on their chin, as this is often a sign that they are listening intently? What is their body language telling you? Are they slumped in their chair? Are they leaning back with a bored expression? If so it is up to you to reconnect again by changing your voice, body language or content.

Articulating what you see

This is a coaching technique that is very effective when speaking in public. If you see that your audience is either with you or against you, tell them what you are seeing. Check back with them if you are right that they are puzzled, sceptical or engaged. If you do this, it shows that you are in the moment and present and will show your audience that you care about them and their reaction.

Actively listen

Another coaching technique. We often listen at a superficial level – just waiting for our turn to speak. But you need to fully focus and show you are listening. You can do this with your body language – nodding your head, putting your hand on your chin, briefly moving towards the questioner during the Q and A session if standing or leaning forward if sitting. You can also do this by repeating back the same words or even using the same metaphors and analogies as the person who is talking. For example, “You say that you feel frustrated, that you are drowning with work, …..”

Pathos, pathos, pathos

As Socrates said if you want to really influence someone you have to have logos (logic), ethos (credibility) and pathos (stir emotion in the audience). You can read more about this in a previous blog.

Many of the people I coach and train shy away from stirring emotion in a professional context, but if you can add a dash of storytelling in your speech or remarks, you will immediately build a connection with the audience as since childhood we have been hot-wired to love stories.

All of this takes courage.

As you can see from this diagram about building rapport, if you move beyond the cliché and facts and start to share beliefs and opinions, you will build rapport. However disclosing more and increasing trust, does come with risks.

But if you want to have impact and influence, and it is done well, then I believe it is a risk worth taking.

by Claire Doole | Sep 4, 2018 | Blog

I was at a conference recently where during the Q and A session, the moderator failed to stop a woman from sharing her life experience as a refugee with the audience. Interesting, as it was how she ended up in Oxford from Myanmar, it was not relevant to the subject of the panel.

As the audience became restless with many rolling their eyes, the moderator did try to interrupt and ask for her question. She said she had no question but thought the audience should know about what she went through!

This made me think of how important it is as a moderator or as a presenter that you handle effectively the Q and A session.

Below are some tips based on my experience as a moderator and presenter who trains in both disciplines.

The audience member, who doesn’t ask a question, but makes a comment.

- Make it clear before you take a question that you want a question not comments.

- Take a leaf out of the book of Christiane Amanpour, the doyenne of CNN, when she moderated a panel at the UN in Geneva.

It is a technique that I find usually works but sometimes as Christiane discovered, it fails to deter the persistent. If this happens to you, you must wait for the person to draw breathe and politely interrupt for the sake of the audience and the panel members, as Christiane does here.

However, you may find, as I did, that certain audience members believe they should have been on the panel and therefore want to share their experience. This is fine as long as the organisers let you know beforehand that someone wants to intervene with a comment.

Handling the audience member who rambles

This happened to me during one of the first panels I moderated. The culprit was sitting right in my line of view so I went to him first. He made no sense as he started to read long passages from a text. I looked at the panellists to see if they understood, but found they were just as nonplussed.

I asked him to get to the point, but he continued to ramble. As the audience began to stir in their seats, I politely told him that we would answer his question in the break.

- Don’t wait until the audience become impatient before asking the questioner to clarify. If they don’t, tell them the panellists will answer their question after the event.

- Ask the organisers beforehand if there is anyone in the audience who is likely to make comments, or speeches. In this case, the person in question was a serial offender and had previously been asked to leave by security when he kept on talking without getting to the point!

Handling the audience member whose English is not understandable

This is my weak point. I speak French and German and am well aware how difficult it is to ask a question in public in a foreign language. I can be too indulgent and try and help the person too much to make their point.

- Seek clarification once, paraphrasing and checking back with them that you have understood.

- If this fails, ask if anyone in the audience can translate the question for the panel.

- Ask the organisers beforehand to provide simultaneous translation if they think the audience will benefit.

Handling the hostile questioner

In my experience this is more of an issue for the presenter/panellist than the moderator. However, the technique is similar.

- Listen actively – try to understand what they are really saying/mean and feel.

- As the moderator, you should understand and acknowledge their concern. As the presenter/panellist, you could reformulate the question positively and answer with what you know or believe. You can also involve the audience and ask their view.

- Closure – check back as the presenter/panellist or in some cases as the moderator that you have answered their question or addressed their concern.

Often people are nervous about the Q and A session, but if you take control you will earn the respect of your audience, panel and the organisers, not least because you have kept the event on time and on track.

If you would like more tips on handling the Q and A session as a panel moderator or when giving a presentation, do attend one of my moderating or presenting trainings.

by Claire Doole | Jul 16, 2018 | Blog, Speechwriting

Recently, I coached the head of a large Swiss NGO for a series of speeches she is giving at a popular summer forum.

We worked on a structure and delivery that holds the attention of a global audience from different backgrounds – academic, non-governmental, diplomatic and corporate.

What the coaching reminded me of is that the theories on memory recall developed by a German Professor during the last century are still valid today. Namely, the ability of the brain to retain information decreases over time.

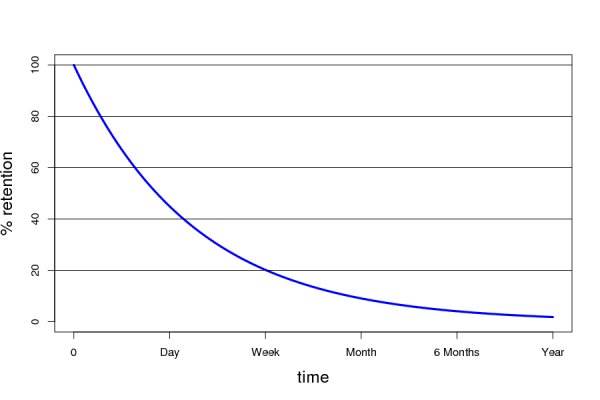

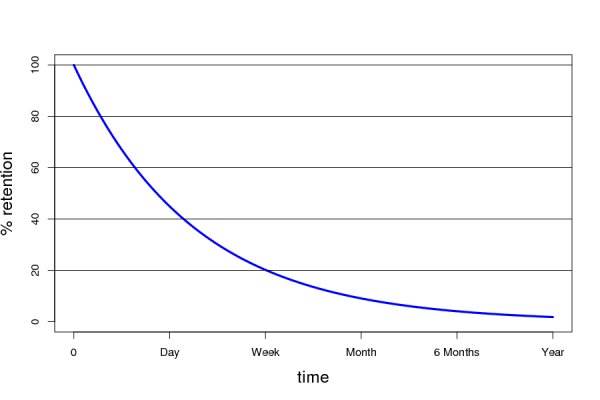

Professor Hermann Ebbinghaus developed the “forgetting curve” which shows that the sharpest decline is during the first 20 minutes and then it levels off after 1 day. The speed of the decline depends on a number of factors such as how easy, visual or relevant the information is to retain. However, on average as the graph below shows people only retain 40% after the first day.

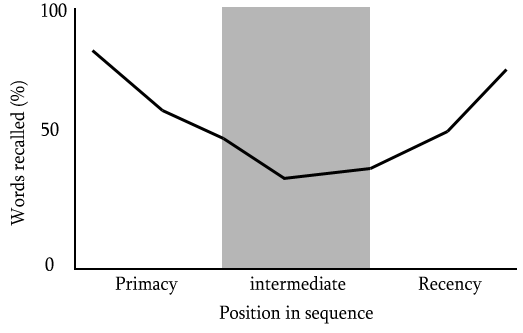

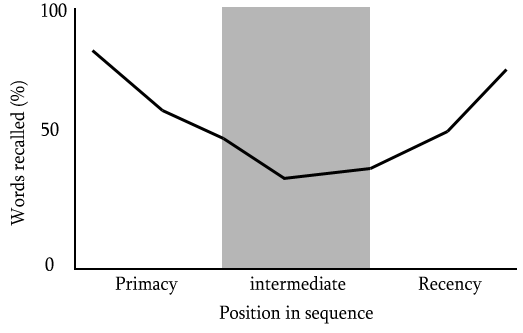

He also developed the concepts of primacy and recency – that we remember the first things and last things we are told with a good chance of forgetting much that is in the middle.

Theory into practice

Armed with this knowledge, she constructed a speech that put the overarching key message in the introduction and then developed 3 related key messages in the body before recapping them at the end.

So did the audience remember the key messages?

I asked people at the forum a couple of hours later and they clearly remembered the introduction – about the rise of xenophobia and restrictive immigration policies in Europe and the US and the call for fundamental rights to be respected.

However they only remembered the messages in the body of the speech when prompted. This may have been because the introduction focussed on a problem that was familiar to the audience and the body on innovative solutions to that problem.

Whatever the reason, it showed that when writing a speech the author has to frontload their key messages to be sure that they are remembered.

The next day, I asked several people what they remembered and true to Ebbinghaus’s theory they recalled the introduction but even less than the day before. The explanations ranged from battling jet lag, the time of day (late afternoon), listening to a foreign language to the temperature in the room (28 degrees outside).

When I tested their recall of the other opening speeches, the results were dismal. They remembered very little a couple of hours after and nothing on the second day.

It has to be said that I remembered very little either, as the speeches were not audience centric and certainly not structured according to the Ebbinghaus principles.

So, however engaged and educated your audience may be, it is worth remembering that it is your responsibility as the speaker to hold their attention by delivering a clear structure with memorable key messages.

SUBSCRIBE TO CLAIRE'S BLOG

by Claire Doole | May 27, 2018 | Blog

After a busy month of moderating for the UN, European Commission and trade federations in Brussels and Geneva, plus running how to moderate workshops for public and private sector institutions, I wanted to share my top 6 tips for successful panel discussions.

The common theme is that while a professional moderator always adds some sparkle, it is difficult to wave a magic wand, if the event organisers have not thought editorially about the panellists and format.

Tip number 1

Select the right panellists for the topic. It sounds obvious, but too often panellists are chosen for political reasons rather than for what they bring to the discussion. Even the most seasoned moderators find it very hard to stimulate an engaging discussion with people who don’t have opposing views or different perspectives.

There is nothing worse than a panel where everybody says the same thing. In this case, as the moderator you have no option but to play devil’s advocate. I was once forced to do this during a discussion on refugees. Afterwards, a young student in the audience came up to me and accused me of not liking refugees. I told her that I used to be a spokesperson for the UN Refugee Agency but my role was not to like or dislike but to stimulate discussion.

Tip number 2

Involve the moderator in panel selection. Many moderators are former broadcast journalists, so they can advise on the range of opinions that are necessary for a stimulating discussion. They can also ensure that there is editorial coherence in the programme as the event unfolds. For me organising an event is like producing a radio/TV programme. It takes time, thought and strong editorial skills.

Tip number 3

Follow BBC best practice. As a producer, you never put anyone on air without checking that they were not only articulate but also had something new or interesting to say. You then wrote a brief for the presenter, who worked out the questions and flow of the discussion.

You were normally looking for those who held opposing views, for or against a subject, but on magazine programmes you often wanted a range of views. These could be demographically different (gender, age, ethnicity) geographically (local, national, regional, international) or involve different stakeholders (government, private sector, NGO, trade union, academic).

Tip number 4

Avoid the presentation style format. This is where each panellist has 10 to 15 minutes to present their perspective, ending with audience Question & Answer. This risks death by PowerPoint, and as people rarely time their presentations – a major mistake – they usually go over and leave little if no time for the audience to ask questions. As the moderator, it is much more difficult to stop someone mid-presentation, although I have done this in the interests of good time management and audience sanity!

If organisers/panellists insist then I suggest I ask them a series of prompt questions so that they can talk around their slides. It takes more work from the moderator and the panellists, but it is more dynamic as it is a conversation.

Tip number 5

Be wary of the opening remarks format. Here each panellist takes 5 minutes to introduce themselves and their perspectives on the topic before the moderator poses questions and the audience Question & Answer. Again, the panellists often talk over their allotted time, but even more problematic is that this can easily be too much information for the audience to remember.

This format works if it is agreed beforehand that the speakers are concise and their remarks pertinent to the subject. For example, if they set the scene for the discussion by introducing their project or programme. If they start to explain issues which are going to be addressed later in the panel discussion, this can become difficult for the moderator to follow up without repeating what has already been said.

Tip number 6

Opt for the Question and Answer Format. Here the moderator either opens with the same question for all panellists or rather like the conductor of an orchestra, brings in the panellists one by one at the right moment in the conversation. For this to work the organisers have to have selected the right panellist (see tip 1) otherwise the moderator spends a lot of time trying to join the editorial dots with a disparate group of people!

If you would like to learn how to moderate like a professional, then drop me a line for details of my in-house one-day workshops or one-on-one coaching sessions.

SUBSCRIBE TO CLAIRE'S BLOG